Transmission #67: Human observations, living poems, and indie film economics.

Design, ideas and other flotsam.

Hello and welcome.

OK, so it’s two in a row! As my old bandmate used to say, “Once is a mistake, twice is a riff!”

Hope you enjoy the links. Please do like, subscribe and share this thing around.

x

Marty

I’m building Ciclo Strategy, a platform to help busy organisational leaders create successful strategies and seamlessly operationalise them within their orgs.

If this is something you’ve been crying out for, check out www.ciclostrategy.com or reach out directly.

21 observations from people watching

Shani Zhang • Skin Contact

A wedding painter (yes, there is such a thing) offers her perspectives from her post as an onlooker of human affairs. Beautiful and astute.

I can see when two people are close in a way that blocks their energy from the rest of the world, insulated and intimate and barring others from entering. I can also see when two people are close in a way that supports each other in being more engaged with the world. I admire the couples who are able to inhabit both states: experiencing the kind of connection that doesn’t allow outside entry, and then turning outward and drawing people in together.

It Awaits Your Experiments

Peter Watts • Rifters

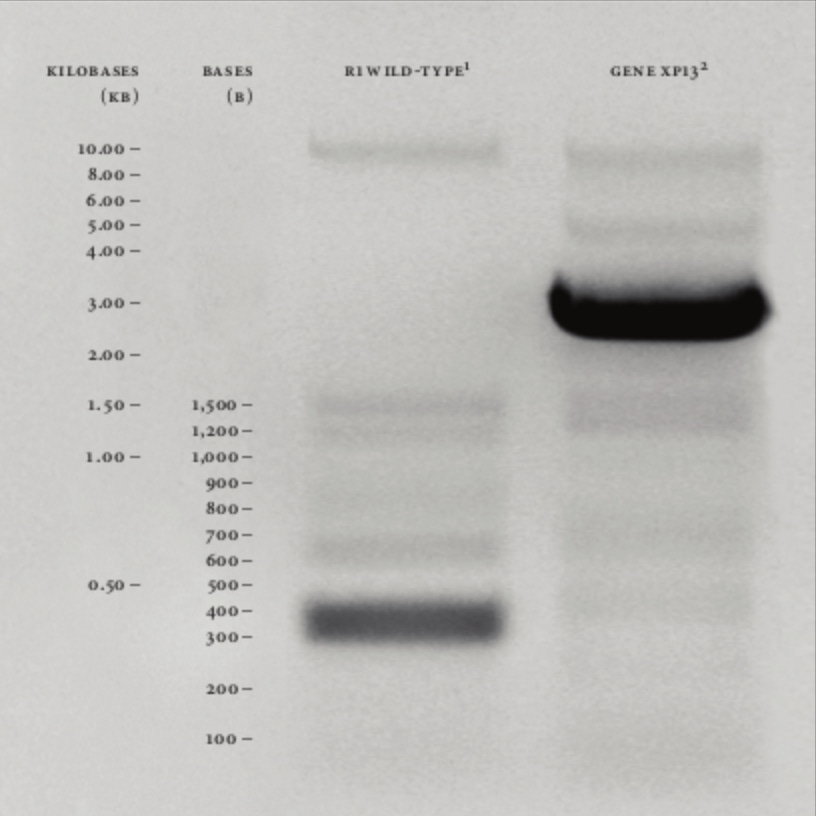

Christian Bök is an unconventional poet. He wrote a book that contains chapters written using only a single vowel (“Hassan can, at a handclap, call a vassal at hand and ask that all staff plan a bacchanal"). And then he spent 10 years trying to encode a poem into a bacterium.

And not just any bacterium. An unkillable bacterium. Deinococcus radiodurans.

From Bök:

Astronauts fear it. Biologists fear it. It is not human. It lives in isolation. It grows in complete darkness. It derives no energy from the Sun. It feeds on asbestos. It feeds on concrete. It inhabits a gold seam on level 104 of the Mponeng Mine in Johannesburg. It lives in alkaline lakelets full of arsenic. It grows in lagoons of boiling asphalt. It thrives in a deadly miasma of hydrogen sulphide. It breathes iron. It breathes rust. It needs no oxygen to live. It can survive for a decade without water. It can withstand temperatures of 323 k, hot enough to melt rubidium. It can sleep for 100 millennia inside a crystal of salt, buried in Death Valley. It does not die in the hellish infernos at the Städtbibliothek during the firebombing of Dresden. It does not burn when exposed to ultraviolet rays. It does not reproduce via the use of dna. It breeds, unseen, inside canisters of hairspray. It feeds on polyethylene. It feeds on hydrocarbons. It inhabits caustic geysers of steam near the Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park.

Anonymous Interview: The Indie Producer

Anonymous • The Vane

I love these kinds of interviews that actually break down what is going on inside an industry and how things work. And of course it’s all driven by economics. This indie film producer lays it out.

Let’s say you produce a movie that has a $2 million budget. How much do you expect to make from that if it goes into production?

In the case of a $2 million movie, I would say maybe $50,000. And when you think about all the work that goes into producing a $2 million movie, and the amount of time that takes, we’re talking about an amount of money that’s lower than what would be considered minimum wage in a city like New York or LA. I’m not going to, like, play the world’s smallest violin for myself, because I know that the artists making that film are getting paid comparable amounts of money. With a movie that small, all the money needs to be on screen.

and

Why do you think it is that movies look worse than they did fifteen years ago?

Oh, man, I can go on about this one. I think there are a bunch of factors at play. The way in which you light digital video is very different than the way in which you light celluloid. There are some brilliant older cinematographers who did amazing work on film and who, to me, would seem to still not really know how to use digital.

When it comes to studio movies, I think a lot of it is just the pipeline created by Marvel and the big comic book movies. It’s so funny how this came about. If you watch Iron Man or the first Thor or Captain America movies, they do actually still look like real movies. There’s a changeover around the first Avengers. And it gets even worse when the Russos come into it, where everything is in this flat Log-C look and the digital elements all feel so plasticky. Robert Downey Jr. didn’t want to put on armor anymore and wanted to just be in his athleisure and have CGI armor plastered over him and get paid $50 million for it. And so those movies ended up creating this digital workflow where they were being rewritten so much, and there were entire scenes that were being relocated after they were shot because they were rewriting the movie after they’d made it, where there just literally isn’t enough time to render the effects and they have to be lit in this completely flat way in order to be transferable in all these senses, in terms of location, in terms of lighting.

There’s a production pipeline that ultimately is adverse to specificity. And specificity is how something looks good. Something looks good when you’re making choices, when you’re being intentional, when you’re planning something out thoroughly.

Thanks for reading! See you soon!