Transmission #23: Superflux, Bullsh*t Jobs, Demography is Destiny, and a Pair of Bickering Italians.

Design, ideas and other flotsam.

Hello. Welcome.

This is Transmissions by me, Martin Brown. Father. Husband. Design Lead at Craig Walker, sometime lecturer at RMIT. Marty to most.

This is an ongoing fortnightly newsletter that collates some of the more interesting stories, links, quotes and other curios that float my way.

If you’re new here, then sign up now to get more of these in your inbox, and don’t forget to tell your friends!

If you’re looking for another great newsletter to subscribe to that’s in a similar vein to Transmissions, check out 10+1, by Rishikesh Sreehari.

Design

Intersection

Superflux

Superflux, the speculative design studio run by Anab Jain and Jon Arden, continue to make essential, challenging, and inspiring design provocations that help us frame the challenges of our time, and point towards what a hopeful future might look like.

After their spectacular exhibition at the Venice Biennale Invocation of Hope, comes this short film, the Intersection, which imagines a future that we seem to be trudging blindly towards.

The AR footage in this film clearly shows a debt of gratitude to Keiitchi Matsuda’s 2016 short film, HYPER-REALITY, which in my opinion is still an eerily likely incarnation of what the metaverse will actually feel like.

(Superflux are also subscribers to Transmissions – hi guys!)

Ideas

One in twenty workers are in ‘useless’ jobs – far fewer than previously thought

Soffia, Wood, and Burchell, Cambridge University

In 2013, the anthropologist David Graeber wrote an darkly funny essay called ‘On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs’ which postulated that somewhere between 20% and 50% of the workforce are employed in what they themselves would describe as ‘bullshit jobs’.

Graeber’s definition of a bullshit job ranges from flunkies (those whose jobs exists only to bestow status on a superior) to duct tapers (those existing to make superficial fixes to problems that could and should be fixed by other means) to box tickers, goons and taskmasters. It’s a hilarious and depressing take on this strange state of capitalism that we find ourselves in.

Graeber expanded his observations into a book in 2018. There’s a sense of overall truthiness and gnawing recognition in his central thesis, born out through the pandemic, that somehow our most ‘essential workers’ – those with the least bullshit jobs – are also the least materially rewarded for their efforts. That somehow the psychic balm of doing bullshit work, must necessarily be more financial reward.

So it’s perhaps some good news then, that at least when it comes to how people value their own jobs, Graeber might have been wrong. Most people actually don’t think they have bullshit jobs, and rather than being as high as 50%, the real rate is probably closer to 5%.

Dr Alex Wood from the University of Birmingham said: “When we looked at readily-available data from a large cohort of people across Europe, it quickly became apparent to us that very few of the key propositions in Graeber’s theory can be sustained – and this is the case in every country we looked at, to varying degrees. But one of his most important propositions – that BS jobs are a form of ‘spiritual violence’ – does seem to be supported by the data.”

Graeber was a brilliant, witty storyteller, and a fierce and important critic of the status quo. His book Debt is a masterpiece. That said, he has his detractors.

Quotes

Let us begin with what might be considered a paradigmatic example of a bullshit job. Kurt works for a subcontractor for the German military. Or . . . actually, he is employed by a subcontractor of a subcontractor of a subcontractor for the German military. Here is how he describes his work:

The German military has a subcontractor that does their IT work. The IT firm has a subcontractor that does their logistics.The logistics firm has a subcontractor that does their personnel management, and I work for that company. Let’s say soldier A moves to an office two rooms farther down the hall. Instead of just carrying his computer over there, he has to fill out a form.The IT subcontractor will get the form, people will read it and approve it, and forward it to the logistics firm.The logistics firm will then have to approve the moving down the hall and will request personnel from us. The office people in my company will then do whatever they do, and now I come in. I get an email: “Be at barracks B at time C.” Usually these barracks are one hundred to five hundred kilometers [62–310 miles] away from my home, so I will get a rental car. I take the rental car, drive to the barracks, let dispatch know that I arrived, fill out a form, unhook the computer, load the computer into a box, seal the box, have a guy from the logistics firm carry the box to the next room, where I unseal the box, fill out another form, hook up the computer, call dispatch to tell them how long I took, get a couple of signatures, take my rental car back home, send dispatch a letter with all of the paperwork and then get paid. So instead of the soldier carrying his computer for five meters, two people drive for a combined six to ten hours, fill out around fifteen pages of paperwork, and waste a good four hundred euros of taxpayers’ money.

– An extract from Bullshit Jobs, David Graeber

Chart of the Week

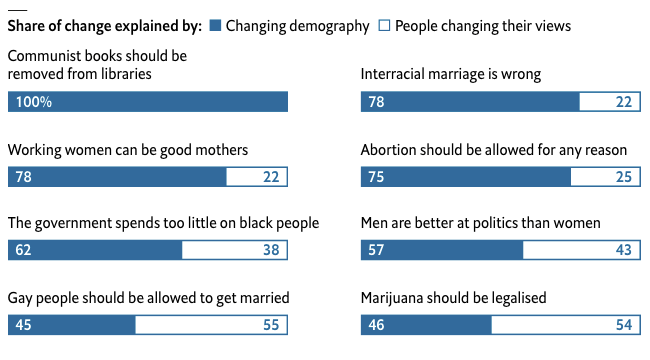

From the ‘Change Happens Slowly, then All At Once’ Dept: this article from The Economist details how many of the long-term changes to attitudes in society can be attributed more to generational change, than to people changing their minds.

Other

🪦 The greatest headstone. Link

🐟 The journey to discover the recipe for the ancient-Roman umami bomb that was garum. Link

🤌 The story of the woman whose inner monologue is voiced, hilariously, by an arguing old Italian couple. Link

-

Short one this time, folks. Till next time!